© 2021 Think Social Publishing, Inc.

What is an education? We decide who qualifies for individualized educational services based on our community’s definition of education—yet most, if not all, states and countries do not clearly define what an “education” actually is. Therefore, our discussions about why a student may not qualify for special education are likely based on inaccurate information. As a speech-language pathologist, I’ve sat in numerous IEP meetings where I’ve been told that the student doesn’t qualify for services because he or she scores too well on tests and is able to perform most of the measurable assessments the teacher assigns in class. Granted, this same student struggles significantly to work in groups, speak in class, ask for help, and develop peer relationships of any kind. Nevertheless, the test scores indicate he is accessing the mainstream curriculum. So, the team determines that because he is able to do most measurable activities, he doesn’t have any educational need. Despite the elephant in the room—this student is clearly not going to be college and career ready by the time he completes high school—he does not qualify for the services he most certainly needs because the decision is based on a nebulous concept of education that equates test scores with being college and career ready.

We recommend, instead, that each IEP meeting begins by providing a clear definition of what education is to determine whether a student qualifies for services or to decide what type of IEP goals are written. To that end, we explore the question of what constitutes an education within our public schools. Then, we propose a strategy for school administrators, education teams, and interventionists to use in creating a working, accessible, and realistic definition of public education that incorporates the present—the school mission statement where the student currently attends—and the future—what college and career readiness looks like based on what CEOs of major corporations around the world foresee will be the required knowledge and skill sets of our future workforce.

Putting a Face on Educational Need

Meet Trevor. Last year, a specialist fought hard to qualify him for special education services in his public high school. The trouble was that his teachers and a counselor had met previously to discuss qualifying him for a 504 plan or an IEP, and he failed to qualify for either because one of his teachers reported that Trevor had given a class presentation (albeit ineptly since he lacks social competence and experiences tremendous anxiety). The take-away from the meeting was, “He’s fine.” His teachers explained that in class he is mostly quiet, but he will talk when asked. Trevor, however, indicated to his private therapist that those classroom situations are almost unbearably stressful for him—a stress level of 9 on a 10-point scale. Both in class and out of class, he spends all of his time by himself; he has no real friends at school. Yet, the school continues to insist that he has no educational need and does not qualify for special education services. They point to how Trevor’s accessing the curriculum, passing assessments, and getting passing grades for the most part.

What they don’t acknowledge is that Trevor is by himself all day long. On an average day, no peers talk to him. No teachers talk to him. No administrators talk to him. He talks to no one. His parents care deeply but they don’t have the necessary advocacy skills; the public special education system overwhelms them. Trevor is isolated, has diagnoses of anxiety, depression, and a late diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. He desperately needs instruction on how the social world works to help him learn how to work (navigate to regulate) in the social world.

So, how do we, the interventionists who work with students like Trevor in public or private schools, help school administrators and those on IEP teams (including parents) or in student study team meetings determine that their education is far more than a sum total of academic and speech and language test scores and grades? How can members of their teams encourage and convince others that we have to do more to help them—and all students—learn how to be contributing and functioning members of society?

A Look Inside Some School Mission Statements

Whichever state or country we are in, whether we use Common Core or state standards or country standards, most schools declare that their primary function is to prepare students for college and career readiness—to create our future workforce and functioning members of society. To publicly demonstrate that they are striving to meet the needs of their communities and state and federal mandates for college and career readiness, schools develop and publish mission and vision statements for achieving this goal. Today, many schools focus on preparing students for global citizenship, with skill sets in communication, collaboration, critical thinking, and creativity—to meet the workforce demands of a modern world.

In a survey of 400 private sector and nonprofit organizations commissioned by The Association of American Colleges & Universities, effective oral and written communication and teamwork skills in diverse groups were deemed among the most important learning outcomes for career readiness. Moreover, in two recent studies undertaken by global technology giant, Google, it’s these so-called “soft skills” that CEOs and employers seek in the 21st-century workforce. In our own random sampling of school district and individual elementary, middle, and high school mission statements throughout the USA, most included language espousing these educational goals for their students in varying degrees of specificity and clarity. Here are several strong, specific examples:

- Discovery High School in Camas, Washington states that its mission for its students is to develop their “collaboration, communication, creativity, and critical thinking skills.”

- The mission of President William McKinley High School in Honolulu, Hawaii is to “maximize the potential of each individual student to become a more responsible, caring and contributing citizen of our society.”

- And Duluth East High School in Duluth, Minnesota strives to “help individuals acquire knowledge, skills, and positive attitudes toward self and others that will enable them to solve problems, think creatively, continue learning, and develop potential for leading productive fulfilling lives in a complex and changing society.”

Some mission statements use vague language that requires deconstruction and interpretation as to what is meant by a contributing member, global citizenship, or college and career readiness and success and which social competencies one needs to achieve these goals. For instance,

- McClure Elementary School in Topeka, Kansas seeks to “prepare all students academically and socially to be productive citizens in a culturally diverse society…equipping them with critical thinking skills…and college and career readiness competencies.”

- Martin Luther King, Jr. Middle School in Atlanta, Georgia works to “prepare students for a globally competitive environment in which students graduate college and career ready.”

- And the Oakland Unified School District of Oakland, California envisions its students “graduating with the skills to ensure they are caring, competent, fully-informed, critical thinkers who are prepared for college, career, and community success.”

Defining Education with Mission Statements

Regardless of language, it’s evident from reviewing a range of mission statements, that to equip students to achieve district goals requires much more than the ability to recall discrete areas of knowledge and standardized test scores. Clearly, there is a need for more precise definitions of what constitutes “an education,” which would also help to define what constitutes educational need.

From coast to coast, school mission statements form the basis of what these schools seek to teach. How then does a mission statement translate into defining “an education”? In truth, most kids, just by coexisting, develop the abilities to do what the school’s mission statement claims—at least they did prior to so many carrying handheld devices that distract them from face-to-face communication and interactive team work. Nonetheless, for students like Trevor, coexisting in a school environment does not, by default, allow them to acquire these abilities—the untestable part of education, the social competencies and organizational competencies that are paramount for college and career preparedness and success, no matter how you slice it.

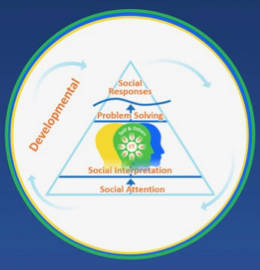

The school may be attempting to reach all students through mainstream instruction, but mainstream education, quite simply, is not providing enough assistance for the student who has social learning needs, who cannot pick up on social cues and create responses intuitively without further guidance and support. We are accustomed to thinking that when a student has high academic test scores, it means he or she is highly qualified or capable of fully functioning in his or her academic world and surrounding community. But what is not being tested at all on these standardized academic tests, what none of these test scores reflect, is the executive functioning and active perspective taking that are required for active ongoing social interpretation and problem solving to foster effective communication, collaboration, team creativity, and group work while being sensitive to others’ needs and reactions. These are precisely among the top 10 skills or competencies that employers are looking for in their workforce, according to a survey conducted by the World Economic Forum. Here’s the catch: there is no standardized test that will measure how someone processes and responds to social information in real time—the foundation of the very skills and competencies with which schools hope to endow their students.

We ask a fundamental question: how can we figure out whether a student has an “educational need” and, if he or she does, how can we define it for the purposes of an IEP?

A Strategy for Defining What an “Education” Is to Decide Whether a Student Has Educational Needs

Here’s a step-by-step strategy that encourages your team to define what is meant by an education, which will help when deciding whether a student has “educational need” beyond what is offered in a typical school day.

- Look at your school’s mission statement.

- The more explicit, the better, but even vague statements are helpful when the language is interpreted and unpacked. Search for even one statement that includes language about character development or being a productive, caring, or contributing member of society, or developing communication and collaboration skills, or college and career readiness. You will have to unpack what is meant by those descriptors and discuss the types of social competencies one needs to show empathy or be helpful to others, to collaborate, or to communicate, for example.

- Talk about the student’s ability to initiate the following interactions:

- Join a peer-based work group

- Ask for help from peers

- Greet peers

- Develop relationships with peers in the class when not working on a group project

- Maintain peer-based relationships outside of the classroom (learning to become a member of the social network in the adult vocational world)

- Use the school’s mission statement to show that an education in this institution is not just “all students can access the information in a mainstream classroom and score well on tests.” It is about teaching students how they can better engage in self-directed behavior, manage emotions, and work as part of a team to accomplish goals that involve what they are learning within and throughout their community. A school’s mission statement often supports a broader, more realistic definition of what is meant by an “education” and helps to clarify whether a student has “educational need.” Changing how we talk about a student’s educational needs changes what we can be doing to foster social and organizational learning to help a student better meet the goals of the school’s mission statement. This shifts the discussion away from standardized measures and grades toward how a student relates to others and functions across the school day. Consider these tips:

- If you are a professional on the educational team, have these discussions prior to an IEP meeting so the team is on the same page and able to focus on what is meant by college and career readiness.

- If you are a parent or guardian for a student, bring the school mission statement into the meeting and ask them to define what an education is in the school and district, prior to discussing whether the student has “educational need.”

- Talk about what it means to be college and career ready.

- Review the World Economic Forum’s report on top 10 workforce skills.

- Discuss the importance of the student joining peer work groups and collaborating as a member of the team as a necessary social competency in both college and his or her career.

- Discuss the student’s ability to create peer networks and develop relationships without adults assisting in the process; this is essential for college, work life, and overall life satisfaction.

It is our hope that bringing this information to the table fosters a more inclusive, well-rounded discussion about what constitutes an education within our public schools. What we propose here is reframing the conversation to encourage a broader exploration into the student’s learning needs. There is no guarantee that the student will qualify for services should you point out these needs, but it’s a strategy for altering the discussion in the room from “Does the student meet the academic standard based on our measurement tools?” to “Does the student meet the standard of what the school is charged with: helping this student be college and career ready and learn to function as a contributing member of society?”

Once the focus of the discussion is redirected, a door opens toward more flexible discussions and IEP goal writing about what the student needs to learn to help him or her during and beyond public school education. Perhaps this discussion may even open a door to helping all students continue to develop face-to-face collaboration—an essential social competency for all.

If you found this article helpful, join our newsletter to receive our latest information and strategies.