© 2021 Think Social Publishing, Inc.

Think about it. Most of our social exchanges, interactions, and time we spend sharing space with others doesn’t happen “around the table.” Rather, we chat with one another while walking, share experiences side-by-side, or even communicate (verbally and nonverbally) when waiting in line. So why do we, as teachers and therapists, spend so much time teaching our students/clients while sitting at a table?

The Social Thinking® Methodology has always encouraged an exploration of how social movement (e.g., walking together, standing in a group, etc.) is related to social competencies. Explicitly teaching individuals with social learning challenges how communication involves more than an exchange of words has been woven into our work from the beginning. We have been inspired from questions from both students and their teachers.

Students asked:

“How do people magically pop into a group at break?”

“How do people talk and walk at the same time?”

“How do kids figure out who to work with in a classroom? How do they join the group?”

Teachers asked:

“How do you teach a student to stand in a line?”

“How do you help a student learn to walk with a group?”

The good news is that one of our most important treatment frameworks – the Four Steps of Communication – directly addresses the physical nature of the social communication process. Imagine you see a group of people you know and perhaps want to join. The four steps we use are to:

- Think. Think about what you know about the people. Consider: Is this a good time to interact or join the group? If so, then…

- Establish physical presence. Move toward the person or group to indicate you intend to join in or interact with them. Look for a natural opening, a space between people that you can move into. This seems obvious, but many of our clients struggle with this step and may start talking to the group when too far away!

- Think with your eyes. As you enter the group, bring your eyes up to acknowledge the others. Then, use your eyes to track who is talking and what the group is talking about. Think about what they mean by what they say and based on where they are looking. It is important to note that others are noticing your eyes too, to see if you are following the group dynamics.

- Use language to relate. Now is the time to start talking. You have thought about who is in the group, you’ve moved your body into the group, and you are using your eyes and brain to track the interaction. You can now use your language to relate to what others may be doing, saying, or thinking about.

We have written quite a bit about teaching these four steps in some of our free online articles and in our book, Thinking About You Thinking About Me. Why? It’s because our social competencies extend far beyond using language to connect with others. Many times we’re socially communicating without words: the way we stand, use our bodies, where we turn our eyes and head, etc. We have to talk the talk and (literally) walk the walk of communication too! Our physicality is embedded in the social communicative process.

As we’ve often stated, Social Thinking is something we do 24/7, no matter where we are, what we’re doing, or who we’re with (or not with). Given our focus on teaching greater social competencies, we thought it a good time to talk about some ways we can incorporate movement and physical actions during teaching. In this article we’ll share six tips and strategies for doing so, organized by working with young children vs. older individuals and adults. In the final section of this article, we align the information with educational standards, providing fuel for how we can encourage getting up and away from the table and incorporating more dynamic social communicative learning in IEPs and 504 plans.

Social Communication has Many Moving Parts – All Happening at the Same Time!

Before we get to the tips and strategies, let’s pause and think about some of the basic Social Thinking Vocabulary concepts that relate to movement, physicality, and being part of a group. They include:

- Think with your eyes (using our social observation abilities to figure out what’s happening around us)

- Keep your body in the group (using our bodies to demonstrate our interest in being part of the group)

- Keep your brain in the group (using our brains to pay attention and stay connected through adding thoughts, making supportive comments, or asking questions of others)

We call these “basic” Social Thinking Vocabulary but nothing seems basic to our students when everything is happening lightening fast and at the same time during group interaction. Our job as interventionists is to break apart and teach sequentially the many social lessons that our students/clients have to incorporate simultaneously. The good news is that’s what movement allows; we can encourage and teach students how to process and respond to this synergistic process!

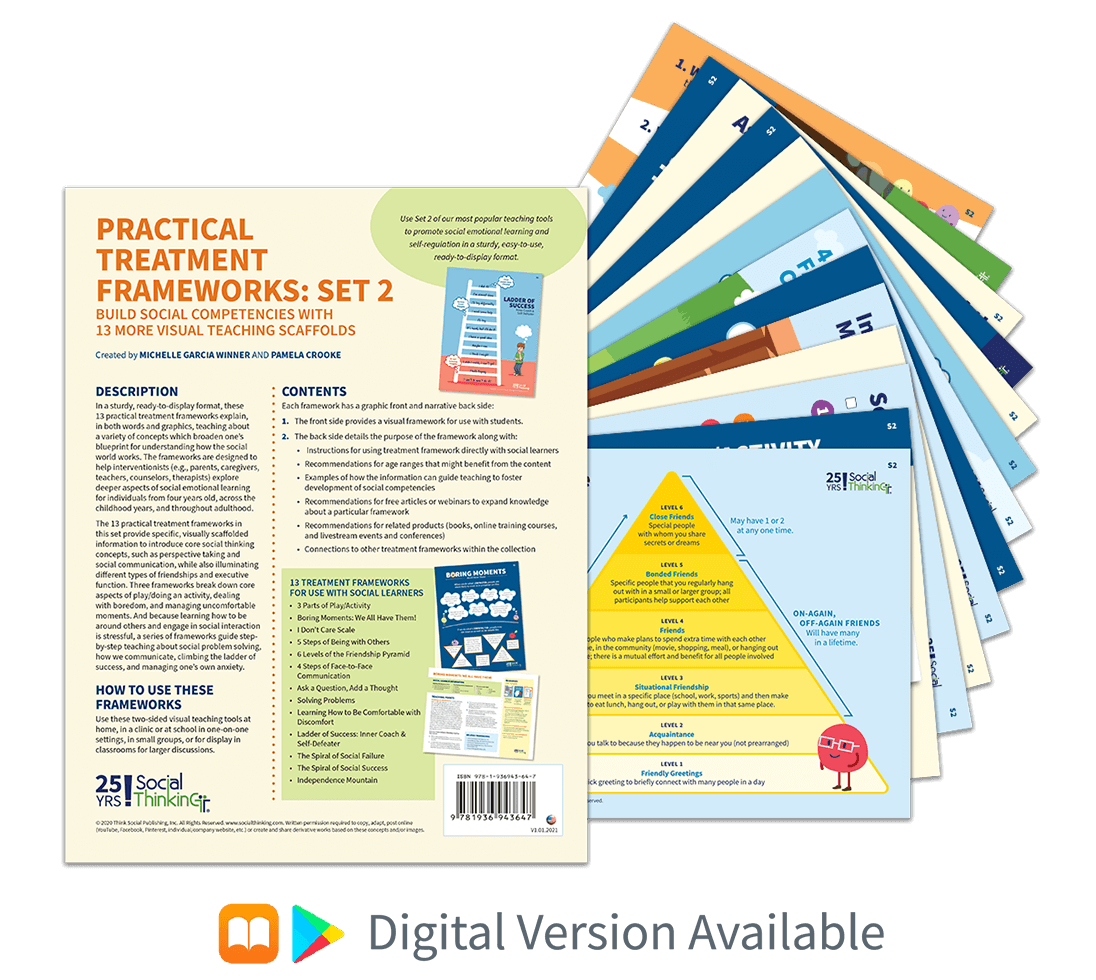

If you’re not familiar with these basic Social Thinking concepts, it would be a good idea to first learn more about teaching them, through any of these products we offer:

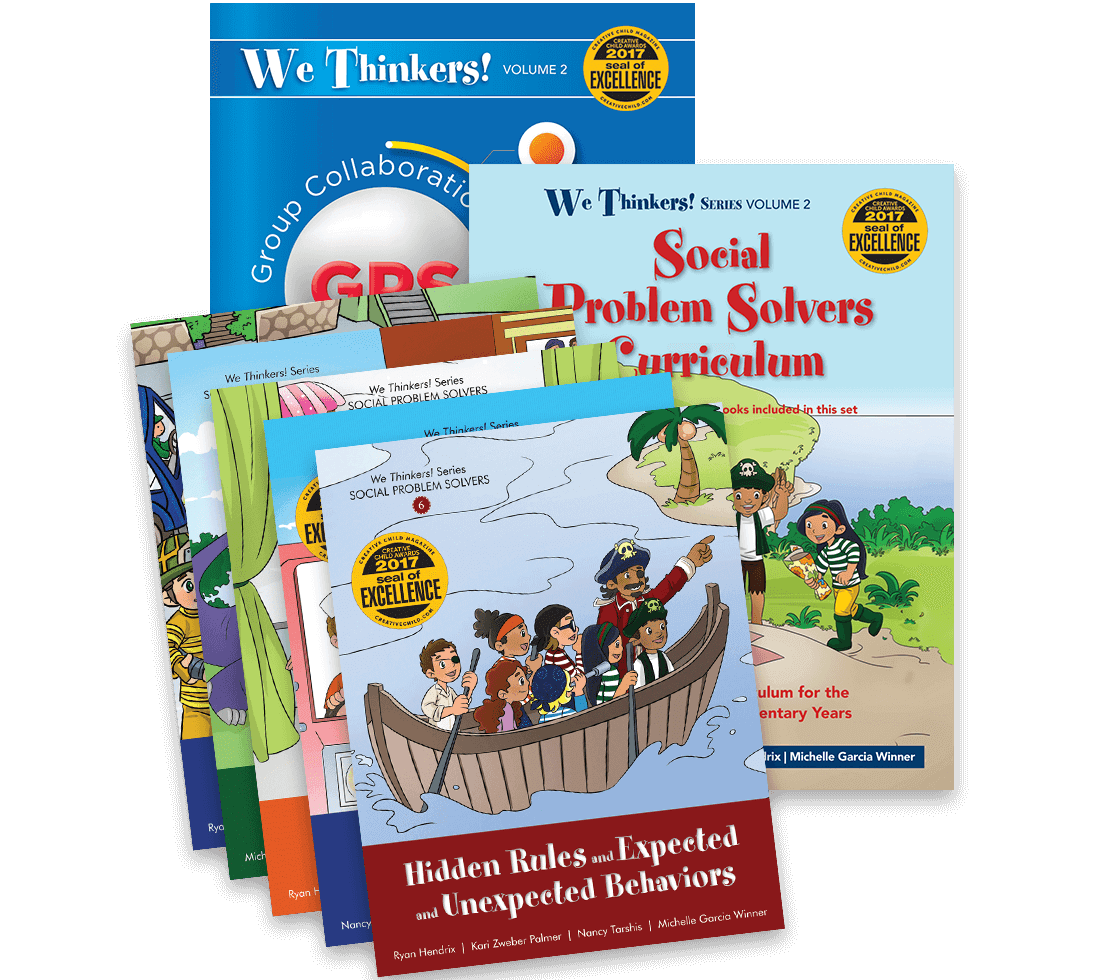

- We Thinkers! Volume 1 & Volume 2 (for early learners)

- Think Social! A Social Thinking Curriculum for School-Age Students

- Social Thinking and Me (two-book set), geared to individuals ages 9-13

- You are a Social Detective!, geared to students ages 4-13 depending on level of social abilities

To follow are six tips for incorporating lessons on physical presence into teaching younger students, followed by six tips for teaching older students.

Six Tips for Incorporating Movement When Teaching Social Thinking to Younger Individuals

For younger kids, use Social Thinking Vocabulary to teach awareness of group dynamics and group activities usually taken for granted (e.g., standing in line, walking in groups, and standard group play games). In doing so you can help children understand that we use our social brains during all sorts of situations and the concepts being learned are not reserved solely for social conversation. Of course, with any of our concepts and strategies, take the time to teach the concept(s) deeply and practice them across various settings before expecting students will be able to do them without prompting or assistance.Note: Social Thinking Vocabulary are denoted below by italics.

- Follow the Leader. Although considered a simple game, this activity is challenging for many of our students because it requires using several social concepts at the same time to imitate what peers may be doing. Look to teach these concepts to help children be successful during the game: think with your eyes, keep your body in the group, and read the group plan. This game encourages social attention and social self-awareness. Both are a part of many social emotional learning (SEL) curricula!

- Red-Light Green-Light. This is a game where thinking with your eyes is the key! Both followers and leaders need to think with their eyes to keep the game moving. Followers also need to keep their bodies in the group and read the leader’s plan.

- Four Square (Try a simplified, slowed down version using larger balls). This game requires your students to think with your eyes, read the plan (motive) of others, and keep your brain in the group. In fact, maintaining focus on the game (brain in the group) is the only way to avoid getting accidentally hit by the ball.

- Lining up, standing or walking with the group. When standing in a line, teach students which behaviors are expected, so everyone can follow the group plan and keep their body and brain in the group.

- Take turns having each student stand with the teacher and notice who is doing an expected behavior while they stand in line. Having students observe the group as they are standing encourages each student to see that a group is a collection of people who use a set of behaviors to cooperate as part of that group.

- You can do the same type of teaching as students move as a group, such as when they are walking together across campus. Keeping your body in the group while moving may be challenging for some of our students who are not strong social observers. They may walk ahead or lag behind. Consider using peer buddies who can prompt them to keep their body in the group. The more students use language to talk about what they notice when students follow the group plan, the more students develop meta-awareness of themselves as a member of the group!

- Keep in mind that many of our students are “me thinkers” instead of “we thinkers.” These Social Thinking concepts won’t come naturally for them and will require more practice than you may think necessary. Self-awareness that each of us is a member of a group (whether that’s two people, two hundred or anything in between) is at the heart of functioning socially. We live in a group thinking world. (Our two volume series, We Thinkers, teaches about these concepts as well as introduces many more activities that encourage movement while students learn about the social world around them).

- Team Sports: Consider how team sports, for example soccer, incorporate all the previously mentioned Social Thinking Vocabulary alongside a healthy use of nonverbal and verbal communication with teammates during game play. In fact, most organized sports require complex social observation and social processing to keep expected/unexpected actions in mind, scan the playing field to get the big picture of how play is unfolding, to keep one’s body in the group in a fluid, moving way, etc. Thinking with your eyes helps players look for signals from other players, notice where the ball is, and follow the group plan to know what to do with the ball (in relation to the other players) if it comes their way: kick, pass, go for the goal, etc.

- Social Detective (Social Spy for older kids). Having students move away from the treatment table is really the only way to develop and practice social observation skills in various settings. Be creative in getting individuals to look around at their situation (think with your eyes), pick out the relevant details, and then interpret this information to figure out expected/unexpected behaviors and/or to follow the group plan. A Social Detective Scavenger Hunt is a fun activity to build social observation and interpretation skills in your students/clients.

Six Tips for Incorporating Movement When Teaching Social Thinking to Adolescents and Adults

We start this by saying avoid assumptions about your clients’ social understanding when working with adolescents and adults. Many an interventionist has assumed that their academically gifted adolescents and adult clients know how to enter and exit groups, walk with their peers, turn and talk to them before class starts, find a group to work with on projects, etc. The fact is that many very intelligent people with social learning challenges just don’t know how to do these things, despite their age or vocational status. The tips that follow can pave the way for greater understanding of their needs on your part, and the opportunity to create more explicit teaching for them. Use these ideas during structured and unstructured social skills/social learning groups. And, keep in mind that many of these individuals may experience social anxiety and just don’t know how to talk about these challenges.- "Your brain just makes this hard." Some of our more academically strong adolescents and adults will truly be taken aback with the idea of having to learn basic social interactions, such as getting in and out of groups, greetings, or chatting while moving. The fact that it’s hard for them to learn makes it even worse. We try to alleviate some of this stress and anxiety by explaining things in a more rational, logical way: we all have our strengths and weaknesses. Start by celebrating the types of learning that are easy for them (e.g., math, science, technology) and explain, “Your brain makes some types of learning easy for you and, relatively speaking, your brain just makes this social learning hard.” Our clients report that this wording helps them see their strengths, while embracing their learning differences. For example, some clients feel awkward being away from the safety of the treatment table or don’t know what to do with their hands and body when entering in, standing, or exiting a group. As we work with them they learn that treatment groups are a safe place to practice, free of any consequences that may happen during real-time social interactions.

- Use role playing and improv activities liberally. This can take the focus away from their own struggles while exposing them to a range of different physical movements and nonverbal actions that are a part of the communicative process.

- Use Social Thinking Vocabulary to anchor and direct individuals’ attention to the dynamics in the group, but use teen or adult friendly forms of our Vocabulary terms. For example, when up and moving around the room, use phrases like “check it out” and explain that we think with our eyes to observe (check out) and interpret what’s happening with others as they move and interact with one another. Other variations of Social Thinking Vocabulary for teens or young adults include: “Hang with the group” (keep your body in the group), “Zone in/zone out” or “Stay connected” (keep your brain in the group), “What’s the plan?” (read the group plan), or “Jump in” (add a thought or ask a question). NOTE: The teen-friendly terms listed above must be carefully taught and clients should understand the connection to the corresponding Social Thinking Vocabulary as well as the underlying meaning before using them in role-playing or improv activities.

- Vary the roles. Give group members the chance to experience and practice as many different interaction roles as possible. Each person can practice being an active member of the group/interaction, an observer of others, and even a judge or commentator. Explain that whether or not we have “good social skills” is a judgment from others—we don’t usually get to judge our own social abilities or challenges. Teach individuals how to give feedback to others in the group in an expected manner and have the group develop their own group norms for how to give and receive feedback in a safe practice environment. Students/clients should start by giving only positive feedback to one another. “Katy stayed with the group and stayed connected—she didn’t zone out once. Good job Katy!” After group members have gained some competencies and practice, coach them on how to give constructive feedback that is clear and concise. For instance: “Katy stayed with the group and stayed connected. She zoned out briefly once but caught herself and jumped back in, adding a couple of comments. Good job!

- Stand UP! Learning to relate to one another with language is critical, but practice this standing up! One of the first things many treatment professionals do is have their students sit at the treatment table to practice having conversations. While this is fine for the first session or two, once students are somewhat familiar with each other take the exact same lessons and have students stand in groups. In our Think Social! curriculum we have several lessons on teaching how to ask a question, add a thought, and use supportive comments. If the lesson includes reading or written work, do it at a table, but be flexible and follow up with the same type of practice while standing in groups.

- Getting into groups: This is harder for your students/clients than you think! Don't assume they know how to stand in a group when asked. We have had countless experiences asking students to “get into a group” and rather than form a sort of circle, they stand shoulder to shoulder in a line.

- Teach that face-to-face communication in groups often involves positioning one’s body across from another person or standing side by side. Have your students/clients explore how groups stand in circles where members can see and think about one another. Have students practice moving from sitting at tables to spontaneously forming a group in the center of your treatment room or out in the hallway (if your room is too small). Once in a group, notice that some individuals may struggle with physical distance, standing too close to others or standing a bit too far away (often those with social anxiety). Explain that where we stand and how we stand (stiff or relaxed pose) sends little nonverbal messages about how comfortable we are around others. Use role playing and improv to practice how communication can occur side by side as well.

- Give “tips” about how we use our body to send messages. Help individuals become more aware of how their feet, hips, shoulders and head should face others. Explain that their eyes should be tracking others even if they are not looking right into another’s eyes (which none of us should do all the time!). For those who can easily put their bodies into the group, build upon this competency by having them sustain and regulate their nonverbal presence and then add language. To measure progress, develop rubrics to take quick data on both your observations and their own self-reflection.

- Practice movement + language. Passing others in common spaces like the halls, sidewalks or other open areas while simultaneously greeting can be a challenge for many of our clients/students. It is one thing to say “hi” when people enter a highly-structured space, such as walking into a class, yet quite another to comment or greet others while passing. It requires split second timing. Don’t believe it? Try some of the activities/strategies below:

- Start by exploring the many ways that people their age greet one another (What’s up? Hey, Hello, Hi, Morning, nonverbal head nod, wave, high five, etc.). Poll students about which type of greeting they want to practice. Teach that greetings require more than just words when two people are moving. It involves our head position, where our eyes are looking, what we do with our body, etc. Timing, using one’s eyes to think about the other person, and language are all part of a greeting.

- Explain that the next part will be practice where they will be working on timing, timing, timing. Have two students practice the greeting as they pass one another. Have the other group members observe and give feedback. The split-second timing of the eyes, verbal greetings and physical gestures all take practice and some of your “brightest” students will struggle with this the most.

- Assure them that the clinic or group session is a safe place to practice and then ensure that it is. Once students develop competencies, have them video their success on their cell phone, if allowed, to use themselves for further reference.

- Don’t skip teaching greeting on this level simply because your students or clients already know how to greet verbally. There are so many components to the greeting process (for instance, what to say when you see the same person again the same day, or how familiarity or gender roles play into what style of greeting is expected/unexpected). We have been amazed at how hard this has been for so many of our older, advanced students!

- Walking and talking side-by-side:

- The first step is always to build awareness of the “hidden rules” for how people share space while they walk together side by side. Observe and discuss!

- Help students/clients notice that people usually walk at the same pace, their shoulders side by side if talking to each other, and they occasionally glance at the other person - but also look ahead to avoid bumping into things!

- A more advanced aspect to this activity is to have each student initiate a conversation as they leave the therapy room or classroom, so they can practice with others working on the same competency in real time.

- Getting in and out of groups. Once students can maintain physical presence in the group, use their eyes to think about each other, and relate to one another with basic exchanges, we then add how to enter, and eventually exit, the group.

- Entering groups. Start by having three or more students stand together to practice basic conversational exchanges inside the treatment room. Ask one of the group members to leave the space—going out through a door, for instance. As the group interacts for 20 seconds or so, ask the student on the outside to practice coming back into the room with the goal of entering the group. Here are some teaching tips to help explain the process.

- Keep in mind the big picture process: When entering the group, establish physical presence and acknowledge others in the group with your eyes (think with your eyes); use your eyes and ears to figure out what is going on in the group before adding thoughts or making comments. Both thoughts and comments should relate to what others are doing or saying.

- Break it down into components. Teach students to be aware of the Four Steps of Communication by labeling and describing each step as part of your teaching. Have group members discuss the steps to increase their awareness and then have them focus on tracking and reporting on one part of this larger process at a time. For example, when working on establishing physical presence don’t worry about conversational skills. If working on conversational skills, back off on monitoring physical behavior.

- Relate the parts to the whole. Once students/clients have competencies in every aspect individually, then begin putting them together during practice.

- Always remember that your students are working on this cognitively rather than just knowing how to do it (intuitively). It takes more energy and work to figure this out than it does by their peers, so be mindful of the effort and regulate your expectations.

- Exiting groups. Use a similar process as listed above to teach how to exit a group: build social awareness first, teach individual components, then put it all together into one fluid motion. Teach students/clients to think with your eyes to figure out the hidden rules and expected/unexpected behaviors around exiting a group. Here’s how we typically practice this in our clinic:

- Have students get into groups and begin interacting together.

- After a short time, the therapist/interventionist taps the shoulder of one person in the group to indicate it is his/her turn to figure out how to exit the group.

- We teach that sometimes the hidden rule may include finishing up a related statement followed by a comment explaining the departure. Other situations may simply involve a short “gotta go” followed by a gradual turn from the group while signaling an exit (e.g., see ya, bye, wave, head nod). Many of our clients turn abruptly and walk away from the group quickly.

- Teach that exits occur with purpose, but not with urgency (unless there is an emergency).

- Entering groups. Start by having three or more students stand together to practice basic conversational exchanges inside the treatment room. Ask one of the group members to leave the space—going out through a door, for instance. As the group interacts for 20 seconds or so, ask the student on the outside to practice coming back into the room with the goal of entering the group. Here are some teaching tips to help explain the process.

- Shift happens. Again, this may seem obvious but it can be very challenging to many of our students/clients. Teach that we shift our bodies (we adapt our physical presence) to make room for people entering the group and we close the gap when someone leaves. Make sure to mention that groups of people huddled together who do not shift when we approach usually signifies that the group is not open to other people joining them. It is always important for us, as interventionists, to spend time observing social subtleties to better teach the strategies. And students love to hear that “shift happens.” Extend teaching about “shift happens” to sitting. Notice how we shift our chairs when welcoming a new person to the table, or close the space as people exit. We even shift in our chairs based on who is speaking around the table or what is being said at different times.

When is a good time to work at a table?

We try to reserve table time for filling out Thinksheets, when first introducing a language-based concept, or when playing a game that requires materials on a table. However, when focusing on concepts related to social communication in general, it is always best to have the majority of your lessons standing, moving, exploring, observing, discussing – away from the table.

How do we build this into IEPs or 504 Plans?

Academic standards, regardless of where they originate, usually include requirements for students to communicate with peers during the school day. And, although not directly stated, they involve movement in some form or another. For example, students are required to work in groups, cooperate, converse, teach, mentor, coach, present, convince, participate, coordinate, and share ideas. Project-based learning is an excellent example where students must assemble as a group, greet and acknowledge each other, show interest in others’ ideas, share opinions, advocate their point of view, and then participate with one another in an efficient and productive manner. These are all skills that are part of college and career readiness! And, we also expect students to take their peer relationships out of the classroom and into their leisure time (in the work environment adults call this “networking”). When writing IEP goals, 504 plans, or building transition plans into these documents, consider that increasing a student’s social competencies in any of the areas listed above is actually demonstrating a focus on the academic learning standards.

Learning and movement go hand in hand. Teaching toward social and academic competencies involves purposeful movement-based activities for increasing social attention, interpretation, decision making and responding. The social world is always moving, so let’s make sure our teaching sessions reflect this!