Updated: July, 2022

© 2022 Think Social Publishing, Inc.

Have you ever tried to make yourself do something that took a little extra energy to remember or required self-coaching to make it happen? You know, things like exercising more often, or keeping your cool in traffic, or eating more greens. We all “know” what we should do. We read, we pick up tips and strategies, we use sticky notes as reminders, and put actions into our daily planners, yet despite our best intentions and desires, the reality is that we simply don’t always do what we say we will do. Why? Most of us would attribute it to just being human. Some of us would carry the weight of self-blame and procrastination. Few, if any, of us would call our inability to follow through a “behavior problem.” Nor would we say that we have issues with “generalization” because we know what needs to be done and we just don’t do it. Ironically, this is exactly what we do with our students when they know what to do, but don’t always follow through.

Generalization is part of social learning!

Generalization is a term used across fields to indicate when an individual’s response or behavior is produced in contexts where it was not directly taught. Curiously, in education when students carry over behaviors they have learned in school (e.g., math, reading) to other contexts (e.g., home, community), we don’t refer to it as generalization – we call it learning!

Social learning is really no different. Our task is to engage individuals in the social learning process by teaching social thinking concepts and related social skills. In doing so we give them the tools to discover deeper ways of personally participating in the social world, both inside and outside the teaching setting. How? Using frameworks and strategies from the Social Thinking® Methodology, we work to develop stronger insights into interpreting social information, what we refer to as social input. We also focus on teaching individuals social information so that they can choose whether and when to adapt their social skills, use self-regulation of their emotions, and produce social behaviors, or social output. Most people unknowingly use the terms generalization in reference to social output and learning to refer to social input! Hence, it is not uncommon for us to hear from educators and parents that their students have learned Social Thinking Vocabulary terms, are able to name the UnthinkaBots, and/or can talk through Social Situation Mapping, but may not be generalizing across contexts.

If this scenario is familiar to you, please take a moment to re-read the opening paragraph.

Even adults with a strong foundation of social competencies still struggle to achieve and generalize some of our own social goals—even though we can explain their importance and articulate a plan of action. So, why do we think the leap from explaining to doing should simply happen for students with social differences and/or challenges? The assumption is that if they can talk about what to do and show “mastery” (not a term used in Social Thinking) in one environment, why not “just do it” elsewhere? The fact is neurotypicals may take for granted their intuitive social skill use across people and places. There is an assumption about the linear progression of social skills without looking closely at the depth and complexity of what it takes to gain social competencies to meet one’s social goals. Instead, we teach that building social competencies is so more than memorizing social behaviors or social skills. Instead, social learning is a vast and intricate web of learning about thoughts, feelings, actions, reactions, attention, interpretation, and awareness of self and others. Social competencies do not unfold in a linear manner; rather consideration of the myriad moving parts must be a part of our teaching because being social is just plain messy.

In this article we would like to propose another way of looking at the social learning process as one that ultimately teaches about social input and social output across time, people, and a variety of situations. And while we will suggest some ways to encourage the learning process, keep in mind that—from our perspective—teaching social skills is not simply introducing and “reinforcing a desired behavior for generalization.” Rather, the Social Thinking Methodology and its related frameworks, concepts and strategies encourage the social learning process through observation, instruction, practice, feedback and coaching, and self-awareness, self-monitoring, and self-regulation.

Foundations: language and perspective taking

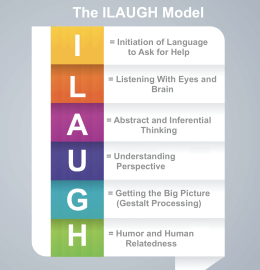

The Social Thinking Methodology is not a match for all social learners. Why? The materials, frameworks and strategies are language-loaded and based in metacognition (thinking about thinking). Individuals who are a well-suited for the curricula and materials are those who currently “talk about thinking” using words like remember, guess, believe, and know, as well understand and use joint attention, and have a basic level of self-awareness and perspective taking. Individuals who struggle with social self-awareness tend to struggle with generalizing as a rule simply because of the role of self-awareness in generalization. In this case, other social interventions and approaches that use prompts and cues may be more effective. So, please note that the information that follows is geared toward those with solid language and cognitive and academic abilities, as well as self-awareness and basic perspective taking.

Generalization right from the start

For those who are less familiar with the Social Thinking Methodology, we always begin by talking about the “why” underlying a social learning pathway. In this manner, we create a foundation for understanding the social world that is not intended simply to increase social skills, but also to fuel their interpretation of social information presented in academics (e.g., comprehension of characters in literature, history, social studies, written expression).

Materials and strategies in the Social Thinking Methodology focus on ways to increase social awareness of over-arching social frameworks (5 Steps of Being with Others, etc.), as well as the subtler social behaviors that contribute to our social competencies (thinking with eyes, body in the group, expected and unexpected behaviors based on the situation, etc.). Our goal is to increase overall social competencies, and not to address, per se, a list of specific skills for specific situations (e.g., sharing toys at home or asking questions during an outing). By focusing on social competencies, we are teaching individuals that their own understanding travels with them from place to place, aka generalization. We use language-based strategies to help individuals think about how to observe, notice, reflect, process, and practice.

What is realistic progress? Our focus is always on helping students improve social interpretations (input) and social behavioral adaptations (output) relative to themselves rather than comparing to neurotypically developing peers. Social learning is always slow and deep. It is filled with nuance and changes with age. The following is an outline of how to engage in a social learning process that includes and naturally fosters “generalization” across people, time and space. Remember: Generalization is not an endpoint; it is simply part of the journey.

9 Ideas for Promoting Generalization

- Make It Personal; Me First! As humans, we are the most motivated to learn information that we think can help our own lives. Too often, social skills programs start by wanting students to change their behavior to meet others’ expectations. We encourage students to figure out that they have expectations of others too. We start by having them figure out what their social expectations are from others. If they feel they are part of the social process, they are more likely to engage in social learning.

- Build a Foundation. Teach how the social world works by providing general frameworks to structure and create a foundation of social awareness and social expectations. These include: 5 Steps of Being with Others, 4 Steps of Communication, and Social Emotional Chain Reaction.

- Make Observation the MVP. We refer to observation as one of the most valuable tools in social learning. Terms like social detective or social spy are used in activities as a way to infuse foundational social knowledge. We then encourage students to begin to observe others, especially their peers, across different situations. It’s important not to start by asking individuals to take note and observe their own behaviors. Instead, have the individual view what others say and do from their vantage point or perspective first. Then, you can begin to encourage attention to situations in which they may have expressed challenges or a desire to learn, such as working together in a peer-based work group, sharing space together in a classroom, playing a specific game on the playground, etc.

- Encourage students to notice that they have clear expectations for others and that expectations flow both ways. Help them to become aware of their strong expectations for others and appreciate that this is a good thing. Understanding expectations helps all of us figure out our role in social situations, even if we are not actively interacting with the people around us.

- Make time for processing and integration. Being able to notice and think about observations is a big step in gaining social competencies. This learning can take time and requires lots of practice. Don’t stop there! Actively encourage and stimulate discussions and processing about their observations. You can also use a variety of materials and situations to observe and discuss social interpretations (e.g., movies, YouTube clips, storybooks, playground experiences, etc.). Keep your eye on helping students form social concepts, rather than focusing attention on one specific skill to the exclusion of others that are undoubtedly connected.

- Explore emotions. Create a foundation for understanding one’s own feelings prior to studying others’ emotions. Given that social interpretations end up impacting how people feel, we always study the social-emotional connection.

- Focus on the Individual’s Own Social Goals. Motivation is a building block for social engagement. Start listening closely to your students to find areas for support based on their own social desires or social goals. Not everyone wants to focus on having conversations or making friends in the initial stages of treatment. Keep in mind, using social competencies is a part of sharing space with others, but making a friend is not a prerequisite for social learning and social skills. Students may express they want to learn to be friendly, approachable, help others, be a good member of the group, or feel like they belong to a group. Be open to their desires and personal goals.

- Remember Motivation. As you find small areas of the social world that your students are willing to work on, you are naturally increasing their social motivation. Most of us like to feel we are heard, so work on building understanding that social learning is like everything else in school: it takes time, practice, and patience. The learning may be slower than in some of their other academic subjects but working toward new social competencies applies to all areas of their lives. Always try to connect to the individual’s life and real world and make sure to recognize their strengths as well as challenges.

- Practice in the Safety of the Therapy or Teaching Room. Remember to teach social information in a safe zone that allows students to explore social thinking and social learning and allow students a place to practice and problem solve the production of social skills.

- Avoid assumptions: Students who state they already “know what to do” often do not. When practicing, have them imagine themselves as they use what they’ve learned in the classroom, lunchroom, playground, home, etc. Don’t underestimate the power of going through the motions in one’s mind – athletes and other professionals do this all the time, so why not when thinking about social.

- Don’t teach social concepts via memorization. Instead encourage the student to think about the bigger picture of the context, the people, what they know or don’t know, what their social goals are, how they will coach themselves though difficult learning moments. For example, let’s say your student states, “I wish I had someone or a group to eat lunch with.” This statement helps you to understand their social goal, which in turn allows for discussions like:

- What type of people do you enjoy being with?

- Who has seemed friendly to you in the past?

- How do people approach others? [Introduce 4 Steps of Communication to support this teaching]

- Provide coaching and teaching with the same Social Thinking Vocabulary and concepts across environments. Important note: Please use careful judgment and do not allow peers to give feedback if they have a tendency to spin negative or tend to make others feel bad. Peer feedback is meant to support and guide, not demean. This means you may need to help your students learn how to give feedback as well as take feedback. Self-reflection and self-evaluation are critical pieces of social learning.

- Build a Coaching/Support Team. Teach parents, professionals, and peer mentors the same frameworks, strategies, and vocabulary to coach in teachable moments at home, in class, on the playground, when hanging out, etc. Hearing and using similar language across different contexts support the continuity of social information across different times and places.

- Branch Out! Once students have made steady and ongoing progress compared to their personal starting point, move your sessions to other situations and people. Walk the halls, talk to others, encourage practice with familiar peers or teachers. Continue to work on thinking and talking about how to engage with the same level of self-monitoring outside the teaching environment (classroom, home, community, etc.). Have students make a plan for when, where, and possibly with whom they are going to practice using what they are learning.

- Celebrate Small Steps of Success! Avoid giving rewards for producing social skills! Social learning takes time and we all like to feel we are making progress and moving forward. Celebrate the smallest of gains but not with unrelated rewards. Have your students talk about what they are proud of rather than simply telling them you are proud of them (That’s nice too, but not enough!). If they can encourage and congratulate themselves, they are developing a stronger inner coach!

Learning social thinking concepts and strategies IS part of the generalization process!

Note: If you are new to Social Thinking, please see many free articles on our website that offer an introduction to our methodology, the core research upon which it is based, and the conceptual and treatment frameworks, strategies, and motivational/developmental tools that it includes.